Jonathan Shapiro aka Zapiro was recently honoured with the Bell Award at the 2017 MOST Awards. The Bell Award acknowledges an individual with a stellar track record of contribution to the sector, and nominees fall outside of the media owner and agency work environments. Few will recognise Zapiro’s face as he prefers to use his creativity and intelligence to further the independence of the Fourth Estate. He is a winner of numerous awards locally and globally for his bravery and skill at using his ever-sharp pen as a weapon to parody, lampoon and ridicule people in power.

With its still recent dark history of oppression and censorship under apartheid, there is a worrying and increasingly narrowing space for robust debate in South Africa today.

The day of reckoning finally arrived for Jonathan Shapiro when he was called up for compulsory national service in the South African Defence Force in the early ’80s.

Shapiro, who grew up in an activist, anti-apartheid home – the ANC’s Gaby Shapiro branch in Claremont, Cape Town is named after his mother – had successfully managed avoid the draft for several years while studying architecture at the University of Cape Town.

But the South African Defence Force (SADF) made it clear that a it would not grant him a further deferment, leaving Shapiro facing stark choices: He could leave South Africa and face the prospect of a lifetime in exile; or he could refuse to go to the army and be jailed for the ‘crime’ of being a conscientious objector, as some brave young men did in those dark days.

But the South African Defence Force (SADF) made it clear that a it would not grant him a further deferment, leaving Shapiro facing stark choices: He could leave South Africa and face the prospect of a lifetime in exile; or he could refuse to go to the army and be jailed for the ‘crime’ of being a conscientious objector, as some brave young men did in those dark days.

Instead he decided he would go to the army under protest but would refuse to bear arms.

“That day I felt I changed into a real activist,” he says.

Shapiro was one of four young conscripts out of his call-up of 7 000 who refused to carry a weapon. Three of them were Christian pacifists, but when Shapiro made it clear that his was a political objection “… they tried to grind me into the dust,” he says.

“But after six weeks they gave up and instead made me a fake rifle with a crude butt and a heavy lead pole for a barrel and made me carry it everywhere.

“I was a walking cartoon, standing up to authority, but doing it in a cartoonish way. It gave me a whole new persona. I was saying ‘I am here under protest’.”

The cartoon-like rifle was intended to make Shapiro a figure of ridicule. But instead he turned it into a joke and used it as a prop to parody everything that was wrong with the army and the South African regime it supported.

The rifle incident was an analogy for his later career as Zapiro, one of South Africa’s leading cartoonists. Except now, in place of his fake rifle, he uses his ever-sharp pen as a weapon to parody, lampoon and ridicule successive post democracy ANC governments and politicians, just as he had done with the apartheid-era National Party.

I’m sitting in Zapiro’s slightly chaotic studio downstairs of his home in an old Cape Town suburb on the slopes of Table Mountain and chuckling aloud as he regales me with the story of his comedic army service. Next to his work light table are a set of his collectible figurines of Nelson Mandela, JZ complete with showerhead, Bishop Desmond Tutu and Julius Malema.

Suddenly he stands up, reaches into a space next to a book-laden shelf and produces the very fake rifle he’s been talking about and poses with it on his shoulder, a huge loopy grin creasing his face.

“I did not have a political home when I went into the army but the UDF (the United Democratic Front, which was in the vanguard of the Struggle in South Africa during some of the darkest days of apartheid) was formed while I was there.”

While he was in the army Shapiro led a double life of reluctant soldier and anti-apartheid activist. He was arrested driving in a protest motorcade and he and his fellow protestors became the first people to be arrested for participating in an illegal gathering while travelling in moving vehicles.

“They didn’t know what to do with me,” says Zapiro, who was kicked out of his unit for insubordination and sent to the navy, where he charmed the officers by gifting them caricatures he drew of them.

“At the same time I was doing posters for the Struggle and stealing paper, tracing paper, paint, and ink. Basically I stealing it from the army and we were using it to produce material for the Struggle.”

The End Conscription Campaign (ECC), formed in 1984 to oppose military conscription and banned a few years later, was also founded while he was doing his military service and it was Shapiro who designed their iconic logo. “Like many other activists at the time, I was a pen for the Struggle.”

At the time black cartoonists were largely absent from mainstream newspapers and many young black artists cut their teeth at the Community Arts Project (CAP) designing and making protest posters, while other worked for the alternative press.

“A lot of the (white) cartoonists then were closet liberals. If you scratched below the surface it was another story. They did not stand up the way they should have,” says Shapiro, a hint of sadness in his voice.

His activism led to him being harassed and detained by the feared Special Branch, which relentlessly hunted down opponents of the apartheid. It is a part of Zapiro’s history that many don’t know about, while others who do choose to ignore it.

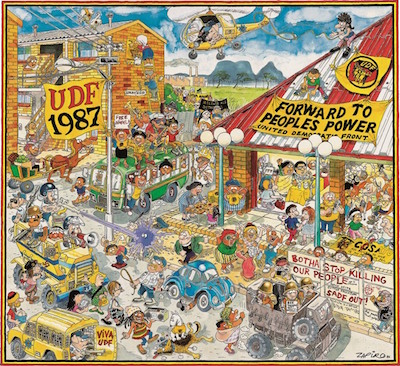

His first major run-in with the Security Police came in 1987 over his iconic Forward to Peoples’ Power UDF calendar featuring leaders of the movement and ordinary people protesting and the police as pigs. After going on the run and evading arrest for 18 months he was finally arrested and spent five days in solitary confinement and a further six days in prison while being interrogated by the Security Police.

His first major run-in with the Security Police came in 1987 over his iconic Forward to Peoples’ Power UDF calendar featuring leaders of the movement and ordinary people protesting and the police as pigs. After going on the run and evading arrest for 18 months he was finally arrested and spent five days in solitary confinement and a further six days in prison while being interrogated by the Security Police.

“They took me to Pollsmoor (Prison) and during interrogation the first question they asked is ‘why do you draw us as pigs?’ I said I draw what I see.”

Zapiro finally landed a cartooning gig at the anti-apartheid South newspaper, drawing two cartoons a week.

“Working in the alternative media I was in a fortunate position of not having to conform. As cartoonists we had far less constraints on us, we could get away with far more than writers.”

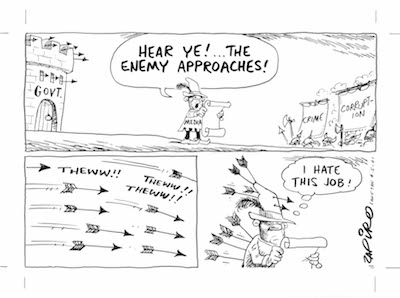

Lampooning, he says, is a very important tool in a cartoonist’s toolkit.

“It’s a very important part of that jester’s space we occupy, using it to knock people off their pedestals. The idea that you could take something into a space where people in power would see it and be laughed at by other people in power is very edgy and very interesting.”

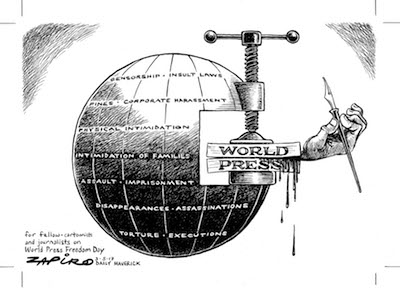

But the Prophet Mohamed cartoon controversy and the deadly Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris have both have had a chilling effect on cartooning and on editors and publishers, he says.

But it’s not just “the fear of crazies” that has led to “a degree” of self-censorship among cartoonists, says Shapiro.

“People are scared of fanatics. But political correctness also plays a role and they fear even minor things. This has led to increased self-censorship by cartoonists because they are increasingly worried about sensitivities and the fear of causing offence,” he says.

With its still recent dark history of oppression and censorship under apartheid, there is a worrying and increasingly narrowing space for robust debate in South Africa today. Accusations of racism on social media often stifle, or sometimes replace, robust debate. As a white cartoonist whose work is published widely Shapiro is often the target of people offended by his cartoons.

He has received numerous death threats as a result of his cartoons, some from “loons” and others he says he took very seriously – but he is at pains to reiterate several times that none were related to his run-ins with President Jacob Zuma.

“I have had lots of death threats and I’ve also had calls in the middle of the night with threats, telling me they know where I live and where my children go to school.”

“I have had lots of death threats and I’ve also had calls in the middle of the night with threats, telling me they know where I live and where my children go to school.”

In the most recent incident, a court was told that Zapiro was included on a hit list compiled by twin brothers Brandon-Lee and Tony-Lee, who are accused of planning acts of terror against American, British, Russian and Jewish targets in South Africa. The brothers have also been charged with attempting to travel to Syria to join the Islamic State.

“People are losing sight of an idea that has been very important over the past few decades that you have no right not to be offended,” he says. “The violence and the real transgression are coming from people who take their religious and other beliefs so seriously and are so fragile in their beliefs set that they can’t tolerate anyone else not having the same view as them. It also comes from authoritarian regimes.”

And, he says, things have become even worse with the advent of social media.

“… some people are living in echo chambers where they hear themselves. This then gets amplified onto a bigger stage where even things used ironically or used to criticise other people are then pounced on, twisted and convoluted, in order to have everyone conform to multiple banal sets of canards.

The most recent controversy centred on his revisiting of an earlier cartoon that showed powerful members of government and the ruling ANC holding down Lady Justice, as President Jacob Zuma prepares to rape her.

This time around he drew the president zipping up his flies as Lady Justice, draped in the South African flag, is held down. To one side a member of the Gupta family prepares to take his turn.

He was sued for R7 million by Zuma after the first cartoon and the case dragged on for four years until the president dropped it on the day before it was due to be heard in court. Zuma had also earlier sued Zapiro for R5 million for a series of three cartoons dealing with the rape charges the president was acquitted of before coming into office. That action against Zapiro dragged on for six years before it was also withdrawn.

On the first rape cartoon Zapiro says: “It was the most powerful thing I could have done and I don’t regret it at all, or for revisiting it. I did always have more of a concern about how women would see it than anything else. I certainly wasn’t concerned at all about how the targets would see it.”

He revisited the rape theme when the ANC, once again, proposed legislation to regulate the Press. That time around he drew Lady Justice who has clearly being brutalised, lying to one side and saying “fight sister, fight” to Lady Press Freedom who is about to be raped by Zuma.

“Cartoonists and satirists and columnists who are prepared to be irreverent or to push the boundaries are not the source of the real problem in society,” says Shapiro. “It is coming from a source people are not prepared to admit to; people who spend their lives waiting to be offended. Some of those people have authority and some are part of fanatical groups or attach themselves to fanatical groups. But to somehow cast the cartoonist or satirist as the provoker of that sort of violence when we are actually provokers of thought is utterly ridiculous.”

“Cartoonists and satirists and columnists who are prepared to be irreverent or to push the boundaries are not the source of the real problem in society,” says Shapiro. “It is coming from a source people are not prepared to admit to; people who spend their lives waiting to be offended. Some of those people have authority and some are part of fanatical groups or attach themselves to fanatical groups. But to somehow cast the cartoonist or satirist as the provoker of that sort of violence when we are actually provokers of thought is utterly ridiculous.”

So do cartoonists enjoy a privileged position in society, I ask as the interview wraps up.

On the one hand, he says, cartoonists do not have any more rights than any other citizen has. “But on the other hand, by convention in a democracy, cartoonists do get to occupy that jester space where you can sometimes say things using hyperbole and hypothetical stuff which can be so extreme as to seem as if you have more rights than other people.

“In other words freedom of expression allows one to be so startling and outrageous and potentially startling that it gives you that rarified position of being untouchable. Speech that should acted against is that which incites hurt or killing but that is not what cartoonists are doing. We provoke thought, even if that thought is pretty outrageous. Others can do it too. We just occupy a space where you can really push the boundaries.”

A bit like the troepie in the apartheid era army who turned his punishment for refusing to carry a rifle into a lampooning protest against the institution that believed it was punishing him.

Here is Shapiro speaking to TMO Live after the MOST Awards about the importance of cartooning and his battles with politicians.

Raymond Joseph is a freelance journalist, journalism trainer, fake news hunter, working on a book at Southern Tip Media.

Photographs of Zapiro by Eric Miller

Cartoons by Zapiro