As the Star Trek franchise turns 50 today [8 September], J. Brooks Spector looks back at it all with wonder and affection.

Is it really possible that the saga of Star Trek is a half-century old? In fact, the first episode aired on US television on 8 September 1966. Sometimes, though, the many voyages of the starship Enterprise have seemed so elemental that the saga’s origins stretch back to the beginnings of storytelling, where the storyteller begins with “once upon a time…”, but in a bright new skin held together by force fields.

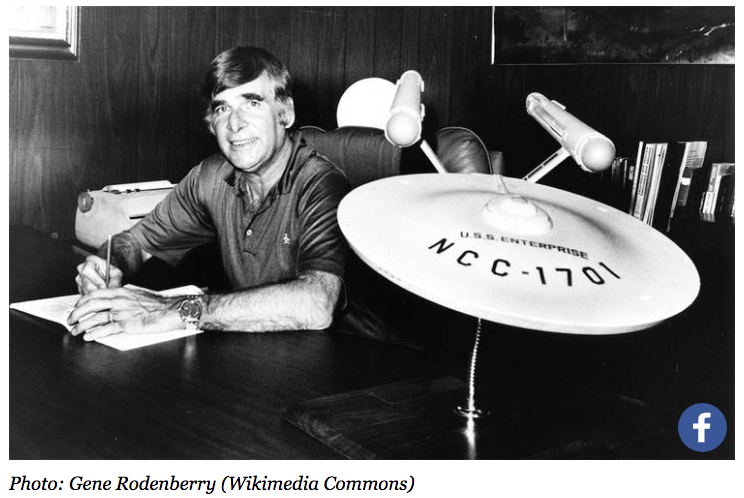

The creator, Gene Rodenberry, and a growing number of the actors who gave life to its characters have passed away, although the actor who breathed life into Captain James T Kirk, William Shatner, seems destined to live forever. But the saga now continues on into new films and a new series, Star Trek: Discovery, due to reach viewers via television screens in just a few months.

A story. Twenty years ago, I was travelling in a minibus, escorting a group of heavy-on-the-maths American economists, en route to a conference on global economic futures to be held in a resort up in the Japanese Alps. These were the kind of people where one of them would write some kind of mathematical gibberish in the air only to have another one erase it with a wave of their hand and then replace it with yet another incomprehensible equation.

Then came the showstopper when one of these visitors happened to mention he had met Gates McFadden recently. Whoa. Equations stopped in mid-scrawl. Awe and admiration rose to near-stratospheric levels inside the minivan. It turned out that she had dropped by his office one day because she happened to be the relative of someone else who worked in the same office suite. Oh, yes, for those readers who do not – yet – know who we are talking about, McFadden played the part of Dr Beverly Crusher on the Enterprise-D of Star Trek: the Next Generation as well as the same character in several films of the franchise.

Of course I had my own little showstopper I could pull out during that same ride through the Japanese Alps. I let slip on that ride that as part of my work in Washington I had personally recruited George Takei – Lt Sulu on the original Enterprise, and the man later promoted to captain his own starship in some of the later films – to become a member of the board of governors of a small but very prestigious US government agency, the US-Japan Friendship Commission. Aha, serious television viewing paid off. While I did not meet Takei in person, I had spoken with him on the phone a number of times and then had an extended correspondence with him about the duties and responsibilities of that office. And when I finally received a “yes” that he would do it, he sent an autographed photograph in response. (Takei actually became very engaged in the commission’s work, mediating between the two nations, and once he had been recruited to serve, he put some real energy and time into the task. A special focus of his attention was on the arts – not surprisingly, given his place in the cinema world.)

Star Trek was first conceived of as a television series back in the mid-1960s, just as the great agonies of the ‘60s were first beginning to make waves in America and beyond. But it was also, still, the America of the latter stages of the space race to the Moon, of a nation that could do pretty much anything it set its mind and shoulder to, and a nation where poverty, racism and even war itself might all be banished soon enough – with enough thought, will, effort and energy put to bear on the question.

In setting his series in motion, creator Gene Roddenberry had given birth to a universe that, soon enough, according to Dave Schilling in The Observer, had defined Star Trekas “…an egalitarian, pluralistic, moral future society that has rejected greed and hate for the far more noble purpose of learning all that is learnable and spreading freedom throughout the galaxy”.

Fans of the many parts of the saga almost inevitably can recall the episode where a planetary-wide struggle between two races – one with the left side of their faces black and the right side white, and where the other race has facial markings in reverse – that is destroying their planet irrevocably. Sadly, despite the Enterprise crew’s efforts to convince them this was an appalling conclusion, the visitors can do nothing to stop the total annihilation. It is virtually impossible to read this story as anything other than a cautionary tale for the futility and destructiveness of racial violence in late ‘60s America and what it might bring.

Star Trek has had its vast impact on millions around the globe, even if such people are not certified (or certifiable) trekkies, showing up at conventions in Star Trek costumes, replete with mock phasers, communicators and tricorders. Of course the funny thing about the paraphernalia of Star Trek is that some of it has helped goose the development of some of the very technology we now take for granted, such as smartphones or iPads – eerily predicted on Star Trek episodes. We don’t have working transporter rooms or apparently faster-than-the-speed-of-light travel to distant spots in the galaxy via wormholes just yet, but such ideas are no longer entirely in the realm of science-fiction either.

And along the way, the science behind SETI and still admittedly remote possibilities of communicating with other civilisations on other planets no longer seems solely to be the possession of day-dreaming post-graduate physics students, nibbling at the ragged edges of science. Just such questions and challenges are increasingly breaking through to the front pages of newspapers and in some reputable scientific journals.

Fittingly, the first test craft in Nasa’s actual Space Shuttle series was named after theStar Trek Enterprise. And actress Nichelle Nichols – Lt Uhura – was given the right to christen that Shuttle as it joined the space fleet. That is life imitating art in a big way, that one. And, well after the end of the original series on television and on into the second life as a film series, Nichols participated in Nasa efforts to recruit minority and female astronauts.

Recollecting her experience at an NAACP fundraiser, she explained how she had been told that another guest at the same event wanted to meet her. As she remembered it:

“I thought it was a Trekkie, and so I said, ‘Sure.’ I looked across the room, and there was Dr Martin Luther King walking towards me with this big grin on his face. He reached out to me and said, ‘Yes, Ms Nichols, I am your greatest fan.’ He said that Star Trek was the only show that he, and his wife Coretta, would allow their three little children to stay up and watch. [She told King about her plans to leave the series.] I never got to tell him why, because he said, ‘You can’t. You’re part of history.’”

Well beyond the way the show influenced individuals, the biggest impact Star Trek has had has been on society as a whole. The various series and the films that evolved from them took on board the idea that, although it was a very near-run thing, humans had found the way past racial animosity and hatred, beyond war and global poverty (and along the way, past environmental destruction and thus how to craft a society that fully integrated technological advances in such fields as nanoscience, artificial intelligence, and revolutions in medicine, among so other scientific challenges).

As Schilling wrote, “Of course, underneath that attitude was the threat of the atomic bomb, the simmering tensions of the civil rights conflict, gender inequality and growing anger at the Vietnam War. Star Trek’s creative brains trust – Roddenberry, Gene Coon, DC Fontana, John DF Black and a who’s who of science-fiction luminaries – was marvellously adept at grappling with these issues and, through the course of 44 minutes plus commercials, convincing the audience that intelligent, progressive minds could work together to solve any problem. Captain Kirk, Mr Spock and Dr McCoy often thought their way out of a situation, rather than simply blasting everything in sight. That’s an inherently liberal position to take: but there are still conservatives among us who project their own ideas on to the series.”

Or, as Gene Roddenberry himself had described it, “[By creating] a new world with new rules, I could make statements about sex, religion, Vietnam, politics, and intercontinental missiles. Indeed, we did make them on Star Trek: we were sending messages and fortunately they all got by the network.”

Much has been made of the idea that the occasionally pugilistic Kirk was more of a Republican than “Next Generation” captain, Jen Luc Picard’s more cerebral Democrat. Well, maybe. Arch-conservative Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz had said last year, “It is quite likely Kirk is a Republican…. Kirk is working class; Picard is an aristocrat. Kirk is a passionate fighter for justice; Picard is a cerebral philosopher.” Maybe he was just projecting who he wanted to be like, however. Still, it seems hard to boil down these characters to simple 21st century American political archetypes. And in any case, on that chart, just where would Voyager Captain Janeway and Mr Spock fit – as the 23rd century’s Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama?

Still, despite Senator Cruz’s desire to see Kirk as a kind of Republican man of action, Captain Kirk was always much more of a lover than a fighter, although he was not above a good right cross or a jujitsu move to put out the lights of some truly bad guy, until an episode finally wrapped up. Moreover, women across the galaxy – black, white, green and purple – found him irresistible. Score one for sexual attraction across the species line whenever James T Kirk was around. And Kirk also just happened to be one half of the first inter-racial kiss ever broadcast on American television, along with Nichelle Nichols as Lt Uhura – amid the racially tempestuous ‘60s.

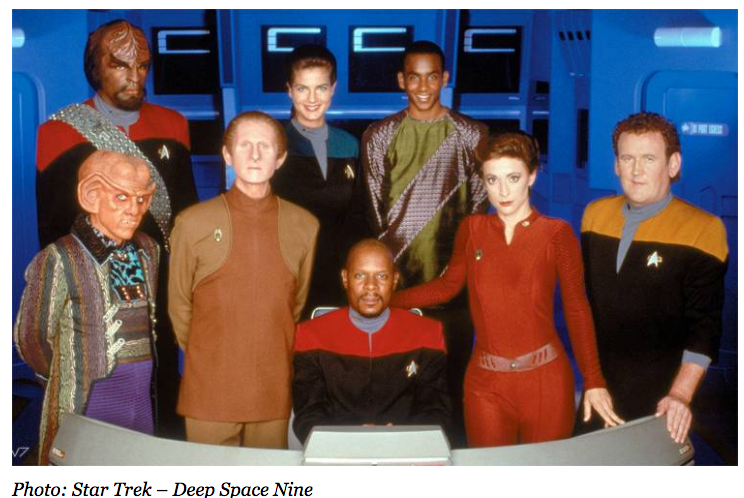

In succeeding series and cinematic instalments, such notions were present as well – whether it was earthlings with a Betazoid, a Klingon, a Bajoran or a Vulcan, although the show’s creators seemed to think close relationships might not work out quite so well with the Ferengi or the Cardassians – and some of the other still more extraordinary planetary races and creatures encountered by predominately human crews on various incarnations of the Enterprise – or some of the other spacecraft used by the crews such as Deep Space 9 and Voyager.

But the various incarnations of the series also posited life forms that were so different from humans and those similar to them that it might be impossible to communicate with them at all by any usual means – forcing logic rather than force to be the pathway to a connection.

Several Star Trek films also took viewers to a universe where science or just human activity had been allowed to run amok, destroying rather than conserving. Terraforming a planet had terrible, destructive results (including the death of Capt Kirk’s only son). The lesson seemed to be that some things might be better left alone, perhaps.

Meanwhile, in another film, an environmental catastrophe in the near future of our current world meant an automated alien craft was now bent on destroying the Earth because the craft’s sensors found themselves unable to communicate with any whales. Unfortunately, every cetacean on the planet had become extinct at the hand of humans a century earlier. That was a problem that was particularly bad news, given the impending destruction of the planet. Fortunately in the case of that particular film, along with some of the entire franchise’s funniest sight gags and other bits of humour scattered throughout the film, a bit of accidental time travel allowed a mating pair of whales to be conveyed forward into the future, just in time to avert total destruction by what might be read as an avenging deity, bent on punishing us all for being so nasty to Gaia.

Like the Star Trek saga, the core trio of Capt Kirk, Mr Spock and Dr McCoy was built along the lines of classical mythological storytelling – in this case, it was a crew of intrepid “sailors” on voyages of danger, excitement, rewards and enlightenment. As Shatner himself described it once:

“There is a mythological component [to pop culture], especially with science-fiction. It’s people looking for answers – and science-fiction offers to explain the inexplicable, the same as religion tends to do… If we accept the premise that it has a mythological element, then all the stuff about going out into space and meeting new life – trying to explain it and put a human element to it – it’s a hopeful vision. All these things offer hope and imaginative solutions for the future.”

Or as film critic Richard Lutz noted:

“The enduring popularity of Star Trek is due to the underlying mythology which binds fans together by virtue of their shared love of stories involving exploration, discovery, adventure and friendship that promote an egalitarian and peace loving society where technology and diversity are valued rather than feared and citizens work together for the greater good. Thus Star Trek offers a hopeful vision of the future and a template for our lives and our society that we can aspire to.”

For some, too, Star Trek adroitly borrowed elements of the world’s classical literature such as The Odyssey, The Aeneid or The Ramayana – tales of travel and extraordinary searches. And, of course, it also contains echoes of the voyages penned by CS Forester of a heroic Capt Horatio Hornblower on his British naval vessels during the Napoleonic Wars.

In the end, Star Trek has been an extraordinarily resilient story that captured viewers, fans and the truly obsessive, and is now heading into its third generation of viewers and fans. It has spawned parodies on shows like Saturday Night Live and a very clever cinematic spoof, Galaxy Quest, that posits hapless aliens kidnapping actors from a Star Trek-esque television show who are at a fan convention in order to help the unlucky aliens fight off a horrific (and very ugly, ill-tempered) galactic menace. They have come to Earth because they have been watching such programmes beamed into space for years and believe it is a description of the real thing instead of TV. Star Trek has even led to a real medical competition, announced in 2012, to develop an actual tricorder medical device that can accurately sense the details of a person’s health and bodily functions, all in one handy device the size of an iPhone, just like Dr McCoy’s tricorder.

And it has generated phrases such as “Beam me up, Scotty” (actually a riff on what Capt Kirk actually said at various times and crises), and the Vulcan farewell actor Leonard Nimoy had appropriated from Jewish mysticism, “Live long and prosper”, which are catchphrases in modern life that even non-fans recognise.

With the newest series about to start on television, and with the third film of the prequel reboot of the Star Trek story already in cinemas, we shall see if this durable franchise is destined to go on and outlive all of its original progenitors and cast members, beyond its perpetual life on cable and satellite TV around the globe.

“Live long and prosper” indeed!

This story was first published by the Daily Maverick and is republished here with the permission of the editor.