South Africa is battling a relentless and rapidly evolving criminal threat: scamming. Far from being a niche problem, this sophisticated crime has metastasised into an epidemic, inflicting financial devastation on citizens and businesses alike. From the classic distraction techniques used at ATMs to highly advanced digital banking fraud and other forms of impersonations, the methods employed by fraudsters are constantly innovating to exploit vulnerabilities in a digitally interconnected society.

In October 2025, infoQuest, a leading South African online research company conducted a survey to assess the extent of attempted and actual scamming among 300 South Africans across all demographics.

This article explores the types of scams commonly used, the incidence of financial loss and other issues related to this epidemic.

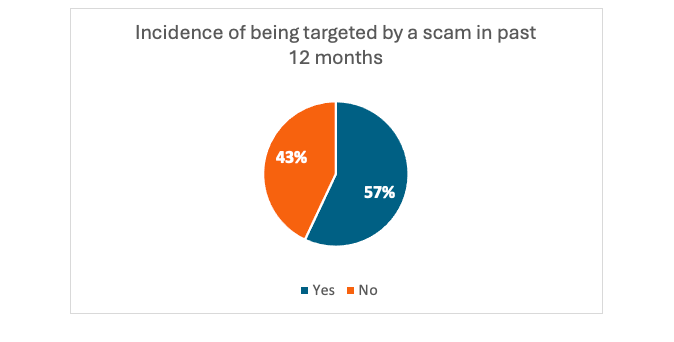

Scam targeting is now a majority experience

The majority of respondents (57%) have been targeted by a scam in the past 12 months, indicating direct exposure to fraud of some sort.

This 57% should be interpreted not as the rate of successful fraud, but as a metric for the intensity of the threat landscape. It confirms the wide-scale industrialisation of scamming operations, which rely on volume and automation to ensure contact with a majority of potential targets.

Interestingly, there were no significant demographic skews in terms of any group experiencing higher levels of targeting – the prevalence is consistent across all demographic segments.

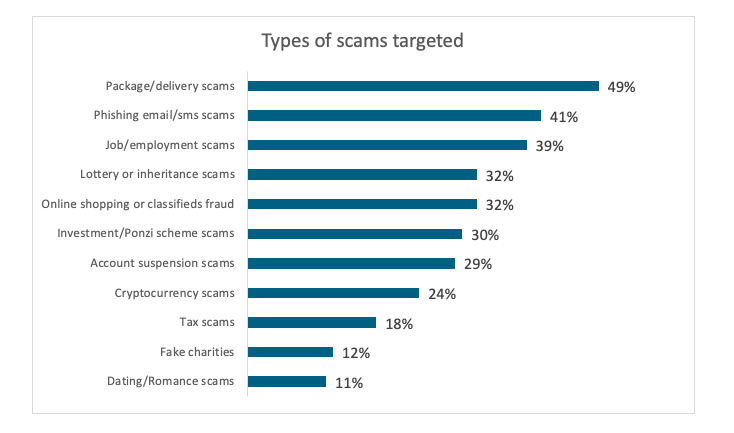

Exploiting the mundane: Fraudsters capitalise on daily logistics and digital trust

Scamming threats that capitalise on common anxieties and daily activities are the most prevalent. Nearly half of respondents (49%) were targeted by package/delivery scams, highlighting the exploitation of routine e-commerce and logistics services.

Closely following are mass-reach digital threats, with Phishing email/SMS scams affecting 41%, signifying that attackers prioritise scale via communication platforms. Furthermore, scams leveraging economic vulnerability, such as job/employment scams (39%), represent the third most common type.

Collectively, these figures underscore a threat landscape dominated by high-volume, low-effort fraud that targets both the logistical points of consumer life and the fundamental trust embedded in digital communication.

Once again there are no significant differences in demographics, indicating that these scams are widespread and make few distinctions between targeted demographic segments.

Each respondent had been targeted by an average of three scams over the past 12 months.

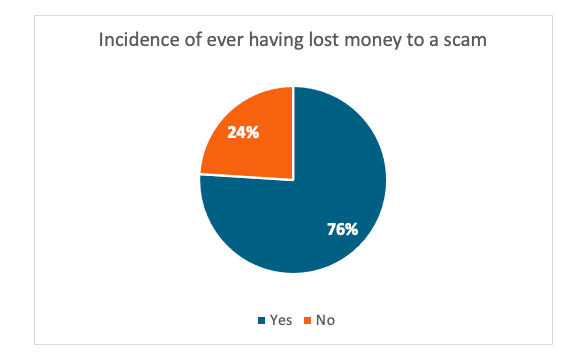

The alarming rate of financial loss to scams: 3 in 4 individuals

The fact that three in four individuals have lost money to a scam reveals an alarming and widespread vulnerability to fraud. This finding shifts the narrative from one of effective defence to one of pervasive victimisation, confirming that scams are not only widespread in their reach but also tragically successful in breaching people’s finances.

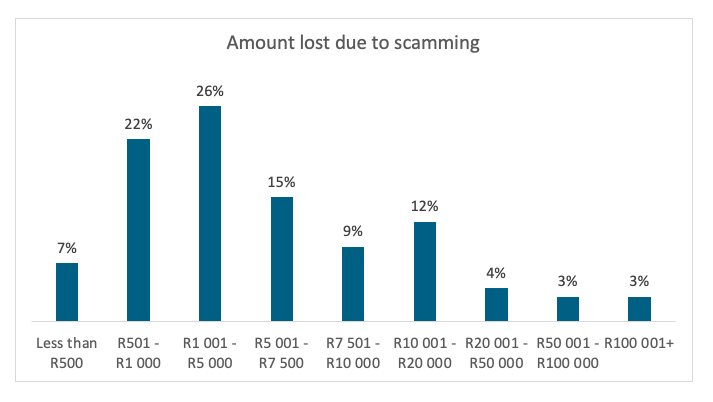

The skewed cost of fraud

The data reveals that the majority of financial losses are concentrated in the lower-to-mid ranges, with the largest single group (26%) losing between R1 001 and R5 000. Combined with the next most frequent loss bracket (R501–R1 000 at 22%), nearly half of all losses fall under R5 000.

While the frequency declines for higher amounts, the chart demonstrates a substantial ‘long tail’ of significant loss, with a combined 12% of victims losing R20 001 or more, including 3% who lost over R100 000.

This distribution indicates that scamming is predominantly a high-frequency, relatively low-value crime impacting a broad base, but simultaneously inflicting devastating, high-value losses on a smaller, yet significant, subset of the population.

Reporting of scams: Implications of the ‘silent third’

One in three victims of scams do not report it. Those that do, use the following channels:

- Their bank/financial institution: 42%

- The South African Police (SAPS): 32%

- The tech/social media platform: 12%

Some of the implications of non-reporting could be:

- Underestimation of the true scope: if one-third of cases go unreported, the official statistics severely undercount the financial and social cost of scams. This could lead to inadequate resource allocation for prevention and prosecution.

- Impeded law enforcement: law enforcement agencies, including the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI), rely on reports to identify emerging fraud trends, link geographically dispersed cases, and ultimately disrupt sophisticated criminal networks. Silence allows these syndicates to operate longer and victimise more people.

- Victim shame and self-blame: a high non-reporting rate often signals that victims feel shame, embarrassment, or fear of judgement, leading them to internalise the loss rather than seek justice. They may believe reporting is futile or that they were responsible for falling for the scam.

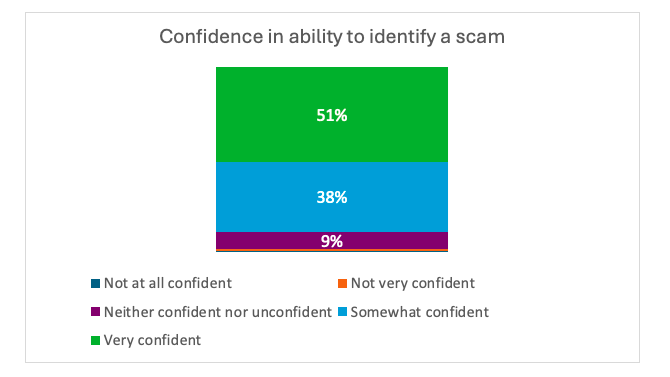

High confidence: The scar of experience or the veil of overconfidence?

Most respondents expressed confidence in their ability to spot scams – perhaps unsurprising among those who have already experienced being scammed and believe they have learned from it. Yet this confidence may be misplaced, as scammers’ methods evolve continuously, leaving even the vigilant vulnerable to new forms of fraud.

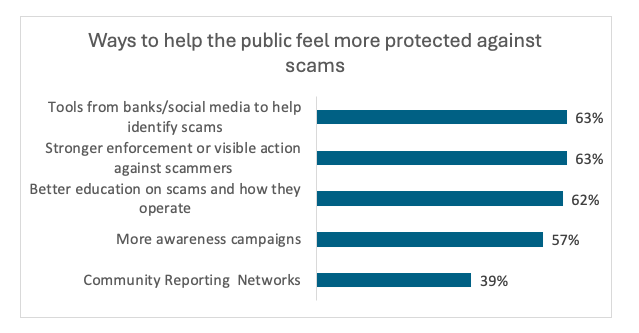

The demand for a dual-pronged defence (technology and enforcement)

Consumers place the highest value on concrete, visible actions from both the private and public sectors. The top two categories are tied at 63%:

- ‘Tools from banks/social media to help identify scams’: This highlights a strong public expectation for technology providers (banks, social media, etc) to invest in proactive technical defences and make scam identification easier for the user. People want systemic protection built into the platforms they use daily.

- ‘Stronger enforcement or visible action against scammers’: This points to a desire for visible justice and deterrence. Feeling protected is intrinsically linked to seeing that perpetrators face consequences, suggesting current enforcement efforts are perceived as insufficient or invisible to the public.

“The findings from this survey paint a sobering picture: scamming in South Africa is no longer a localised crime but a national epidemic of industrial scale and alarming efficacy. That 57% of respondents were targeted within a year confirms criminal syndicates have successfully weaponised volume and automation, turning exposure to fraud into a near-majority experience across all demographic segments.

“This pervasive threat is not just theoretical; it is tragically effective, with a stunning 76% of targeted individuals losing money,” said Claire Heckrath, MD of infoQuest.

The analysis identifies two primary obstacles in addressing this epidemic: underreporting and overconfidence. One in three victims — the ‘silent third’ — fail to report their losses, obscuring the true social and financial impact. Meanwhile, persistent public confidence in detecting scams, even among victims, fosters complacency amid rapidly evolving fraud techniques.

Consumers are demanding a stronger defence – one that combines smarter technical protection with visible justice. They want proactive action from banks and social media platforms, and tougher, more transparent enforcement against criminals.

“This fight can’t be won through individual vigilance alone,” Heckrath said. “It needs an integrated ecosystem where banks, social media companies, law enforcement and government are all held accountable for real safeguards and swift, public consequences.”