That South Africa’s TV soap industry is tough goes without saying. Six-day weeks, 12-hour shifts and 4am calls are de rigueur, and job insecurity is a feature. But soapies are infinitely more profitable than other TV genres.

In early March, Muvhango actress Florence Masebe set off a Twitter storm with a tweet claiming that South African audiences shouldn’t be emotionally blackmailed into watching local films, highlighting the lack of effective marketing as the reason for paltry audiences at cinemas.

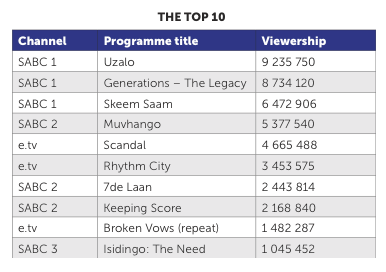

But if viewership figures for a steady stream of local soapies are anything to go by, South Africans clearly love their drama. And our local stories come out tops every time, with all of them beating out even longtime US favourite, The Bold and The Beautiful, in terms of audience numbers.

And the hits just keep coming, with new series in the works, telenovelas hitting their stride – and some transitioning from one form to another.

“Local soapies pull audiences not only because they’re indigenous and follow the winning formula of good guy vs bad guy, but because they’re also relevant, up to date with current affairs and ingrained in the psyche of the community,” notes freelance line producer Michael Modena, who’s worked on various local productions from Mzansi Magic’s Greed and Desire to SABC 1’s ratings champion, Uzalo.

“Local soapies pull audiences not only because they’re indigenous and follow the winning formula of good guy vs bad guy, but because they’re also relevant, up to date with current affairs and ingrained in the psyche of the community,” notes freelance line producer Michael Modena, who’s worked on various local productions from Mzansi Magic’s Greed and Desire to SABC 1’s ratings champion, Uzalo.

Accounting for more than 40% of overall television viewing, soapies are a broadcaster’s bread and butter, and prime time slots across all channels are highly contested spaces for advertisers. These slots, says e.tv’s general manager for new business and Africa sales, Santie Raubenheimer, are not negotiable, with no discount packages available. “Obviously, people buy eyeballs and if the show gets enough eyeballs, it sells out fast,” she adds. Bookings are made on a three-month basis and, with soapies meeting the majority of the market – on all LSM ranges – advertising comes from “pretty much across the board” with a variety of brands wanting to fill the 12 minutes of airtime available during a particular screening, notes Raubenheimer.

But while viewers now have more choice in terms of language or storyline than they did when Egoli, South Africa’s first homebrewed soapie first hit our screens 26 years ago, the proliferation of drama series on an increasing number of channels opens up another nightmare for broadcasters: That of dwindling audience figures – and less ad revenue.

Spreading it thin

“It’s a worldwide phenomenon: As TV channels have proliferated, audiences are more fragmented, with the result being that each broadcaster has smaller audiences – and their slice of the ad revenue pie becomes significantly smaller, which is not good for producers,” points out Harriet Gavshon, co-founder of Quizzical Pictures, who produce e.tv’s Rhythm City.

“It’s a worldwide phenomenon: As TV channels have proliferated, audiences are more fragmented, with the result being that each broadcaster has smaller audiences – and their slice of the ad revenue pie becomes significantly smaller, which is not good for producers,” points out Harriet Gavshon, co-founder of Quizzical Pictures, who produce e.tv’s Rhythm City.

The effect trickles down.

“Our rates as an industry, for providing content, have decreased year on year, so rand for rand, we’re working with the same budgets as 10 years ago – which is extremely difficult; a lot of productions are underfunded because the broadcasters are squeezed.

“I suspect with some that there’s just not enough money to get paid properly – producers are always blamed for it, but they do the best they can to stretch resources – and this, in turn, creates a squeeze on actors and crew rates.”

The plotlines may follow predictable curves, but scheduled screening times, ad rates and production costs all vary from broadcaster to broadcaster. SABC’s R167 million contract with Uzalo made headlines because of the production company’s co-owner, Gugulethu Zuma-Ncube, who is former President Jacob Zuma’s daughter. But, points out her Stained Glass Productions partner, Kobedi ‘Pepsi’ Pokane, who is also managing director of multimedia company Bonngoe Productions, “That political connection worked against us – for the longest time nobody wanted anything to do with the production; we battled to get it sold.”

Timing was the show’s saviour

Timing, he says, proved the show’s saviour. “Nobody was doing an authentic Zulu language series, set in KwaZulu-Natal – that is the biggest audience in the country, so it was a no-brainer for SABC 1; it would have been daft for them not to take the show – but it was a timing thing: often, producers come up with ideas, but don’t always think about the business of bringing it to life.

Timing, he says, proved the show’s saviour. “Nobody was doing an authentic Zulu language series, set in KwaZulu-Natal – that is the biggest audience in the country, so it was a no-brainer for SABC 1; it would have been daft for them not to take the show – but it was a timing thing: often, producers come up with ideas, but don’t always think about the business of bringing it to life.

“Uzalo proved to be a problem we were solving for the broadcaster, to meet its audience mandate.”

Pulling in five million viewers for its first episode, it didn’t take long for Uzalo to edge out the competition.

Today, the soapie often hits the nine million mark, often going head to head for the slot with long-time frontrunner Generations, reinvented as The Legacy.

It also boosted the region’s status as a film location destination – and may have to contend with another battle for audience figures with this month’s (mid-April) launch of Imbewu: The Seed, which is also being shot in Durban and is billed as a thriller. In a move that prompted as much gossip, rumour and speculation as the storyline of any of the number of series she’s been on – think Generations, Hopeville, and Soul City – Leleti Khumalo, who shot to fame in Sarafina, walked away from her lead role as Zandile ‘MaNzuza’ Mdletshe in Uzalo to star in and co-produce Imbewu, an offer she says she couldn’t refuse.

“I’ve known Duma Ndlovu (co-creator of both Uzalo and SABC 2 headliner Muvhango) for the longest time and we’ve always wanted to work together on a bigger scale. About two or three years ago we discussed doing this production, and when we decided to do it, we brought Anant Singh on board as well…”.

Singh, owner of award-wining Videovision Entertainment, would bring his movie experience to the making of the soapie, says Khumalo. “He insisted on doing this as a movie – introducing elements of moviemaking into it.”

Expanding on the telenovela

This element, says freelance producer Frank Perold, is why he prefers the telenovela format. As former head of production at Curious Pictures (now Quizzical Pictures), Perold helped launch Rhythm City, and Ashes to Ashes, and worked on rescuing The Alliance, among others. He reckons telenovelas are a winner for broadcasters and production houses alike.

This element, says freelance producer Frank Perold, is why he prefers the telenovela format. As former head of production at Curious Pictures (now Quizzical Pictures), Perold helped launch Rhythm City, and Ashes to Ashes, and worked on rescuing The Alliance, among others. He reckons telenovelas are a winner for broadcasters and production houses alike.

“It’s a story that has a beginning and an end – you can write it with an end in sight, not like a soapie that’s open-ended. It’s also quick to work on; you can shoot an episode a day. Also, many don’t get shot in studio; you turn a location into a studio, work within those boundaries. So it’s not as pre-lit: the lighting’s better, you get a better look than with studios, which are lit from the top.”

Broadcasters can also budget better for it, with a limited amount of episodes, he adds. “It makes life easier for advertising sales teams and the production company, who know when budget will run out, or whether the contract will be renewed, unlike soapies. On a soapie, if the broadcaster pulls the plug, the producer could be in huge trouble, especially if they’ve revamped a set, or splurged on post-production.

Like Muvhango, Uzalo started out as a telenovela, with three episodes per week. Interestingly, it was advertisers who prompted the series’ evolution into a full-week soapie, says Pokane. “The decision to make the transition came halfway through the first year, when we kept growing… viewership wasn’t pulling back. The advertisers had a lot to do with it; the input from the airtime sales division was the critical factor; they kept selling out on it, and the biggest push came from them, they preferred to keep it running.”

As much as he benefits from the appeal of Uzalo’s success to advertisers, Pokane is not blind to the industry’s lack of qualitative offerings. “What invariably happens is that other types of shows outside soapies and dramas are the ones that suffer, in my view. Media buyers and planners in South Africa tend to go after numbers as opposed to fully interrogating the universe, environments and communities – there are certain audiences on any number of productions to whom brands could be appealing to directly. But advertisers don’t get to them because they take a look at the numbers, then discard shows that aren’t pulling large audiences even though those audiences are perfect for the client.”

The moneymakers

So who are the real winners: actors who make the leap from obscurity to become household names; production companies who squeeze every last drop from a budget that ranges from R12 000 to R15 000 per screen minute to make a profit, or broadcasters who name their price on ad slots that can range from R70 00 to R200 000+ on a 30-minute insert?

No one’s telling, but the figures, though dismal to some, add up to a winning recipe. Broadcasters can add to their tally with sponsorships (Rhythm City, for instance, is sponsored by Assupol), and product placements, but these, according to most producers, are not really a feature in local productions.

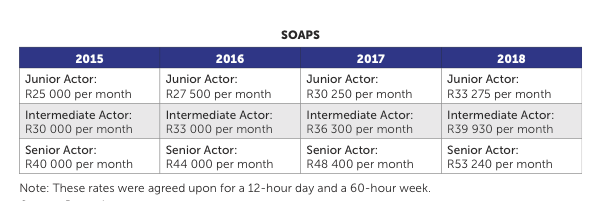

Salaries are a hotly contested issue, with agents like Belinda Kruger of FigJam Agency claiming that only about 10% of producers operating today pay their cast a fair rate. “Fees in the 1990s were more than the fees paid today; everybody is pleading poverty and claiming to be on a low production budget, yet someone is making money,” she asserts.

Pay rates obviously vary, from R4 000 to R5 000 per call for an entry-level actor – “I’m battling to get that now for senior actors, which means something is very wrong” – to R120 000 per month for big ticket stars, confirms Kruger. “That obviously depends on the actor, and those who earn that would have paid their dues – up and coming actors cannot expect that kind of fee,” she says. Yet stories abound of young stars pricing themselves out of the market. “It happens all the time, mostly with younger actors, that won’t listen to the voice of reason and realise they’ve got to be realistic about budget on the table,” says Kruger.

Residuals, which broadcasters pay producers and actors for repeat programming, after a certain number of repeats, is another contested issue. While the SABC and e.tv pay residuals, M-Net doesn’t. “They’re a law unto themselves,” claims Kruger. Generations creator Mfundi Vundla is still embroiled in a fight for this with 16 actors fired from the original series after demanding a salary increase.

Rumour has it that Khumalo quit after salary negotiations with Uzalo producers failed. But the actress says she was offered an opportunity she couldn’t turn down. “It’s a risk, in this industry – most of the time you don’t know if a project you sign on to will fail or succeed. But I wanted to try producing because I want to change things a little bit, to use my frustrations as an actor as an advantage. As a producer, I feel I can listen to actors and the crew, and make sure they’re happy. Then, they deliver.”

She’s already discovered though, that “you cannot think as an actor while you are producing”.

That the industry is tough goes without saying. Six-day weeks, 12-hour shifts and 4am calls are de rigueur, and job insecurity is a feature. But soapies, confirms Pokane, are infinitely more profitable than other TV genres. “They’re more profitable based on volume: the number of minutes you produce – with greater volume your margins are less.”