Critics seem to have been shocked by horror films in the past few years. Of all people, they shouldn’t be, as shock is one of the cheap tricks for which they have always denigrated horror movies.

Shock is easy and effective, but it’s vulgar. And scary movies are an amusement ride that rack up tension towards a peak, then drop us into a trough with a scream. It’s the same ride every time and we loop back to where we began. They are that mechanical.

But films such as Ari Aster’s Hereditary, Jordan Peele’s Get Out, and Robert Eggers’ The Witch have changed that. They have been praised in the mainstream press for their lofty ambitions, their social consciences, and their worthiness. The critical impulse, however, has been to file them away as categorical errors: they can’t possibly be horror films, because horror films are just thrill rides.

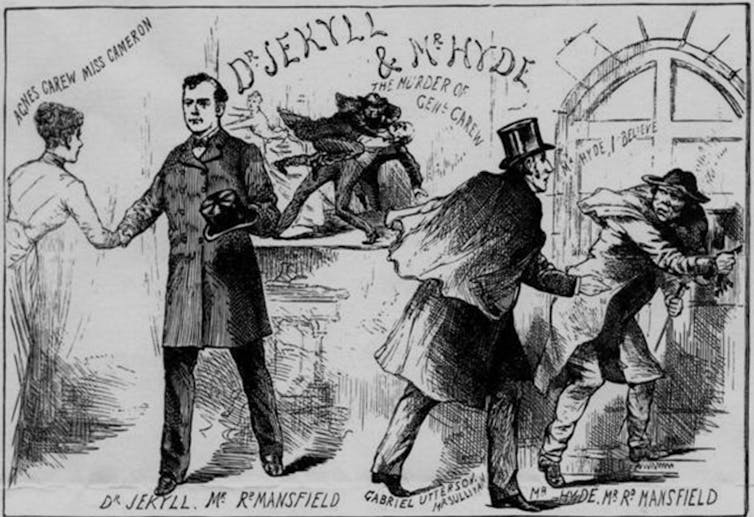

But horror stories have long grappled with deeper themes of human experience. Frankenstein is rich with questions about the meaning of nurture and of empathy. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde explores the duality of man. “Shock horror” films are different, feeling much closer to pornography than art – the story doesn’t matter, it’s about the extremity of what you see. Indeed, after pornography, horror is the highest-grossing genre of film. No wonder critics attempted to move the films they like out of such company and rehabilitate them, as has been done with classic horror literature.

Wikimedia Commons

Prominent articles in the Hollywood Reporter and Washington Post attempted to reclassify films such as Get Out and Hereditary as “elevated horror”, “smart horror”, or “post horror” – all terms that, while they may seem to qualify the genre, still just mean horror. They are films that do the thing that horror films do: through metaphor and fantasy, they reveal a dark truth.

The way we classify films can be misleading. A scary film, for example, is not the same thing as a horror film. A scary film scares you – and a scare takes place in an instant. It’s a “jump-out-of-your-chair” moment. It’s that same chair flying across the room, a door slamming, someone behind you going “BOO!” A scare is always accompanied by a sigh of relief. It’s fun – the thing wasn’t really there. Add enough of them together and you get a 90-minute scary movie.

A horror film, on the other hand, is much longer than that. Horror is the slow, dawning realisation that the worst thing is true. Unlike the scare, there is no relief from it. The scare and the horror are opposite extremes: the scare is just behind you, but the horror is right in front of your eyes.

House of horrors

When the producers came to me with their idea for the film that became my debut feature, The Devil’s Doorway, it could have been a scary movie. They wanted to make a found-footage film – think The Blair Witch Project or Paranormal Activity, films that purport to be unedited footage shot by the characters in the film themselves. And they wanted it set in an abandoned Magdalene Laundry, one of the haunted remnants of Ireland’s recent past, where woman – unmarried mothers, troublesome girls, lesbians – were condemned to live their lives in wash houses run by the Catholic church, kept from society and washing the country’s dirty linen.

In other hands, it could have been a race through empty rooms, pursued by the vengeful spirit of a mistreated girl – all caught on GoPro. That, however, would have missed the horror of the situation, using the history of those places as a mere backdrop for the film’s mechanics, like erecting a theme park there. I proposed we make a horror film instead.

In 1960, two priests enter a working laundry, charged with documenting the supposed Marian miracle that has taken place there. As they gather footage and interview defensive nuns, it becomes clear that something else is going on. However, it is not the Gothic revelations in the film that make it a horror film – rather it is the thing that the two priests really document. There is spooky stuff, but the real horror is the slow dawning for the priests – and through them, the viewers – of the real-life situation that exists and is being perpetuated by the Catholic church and the state that condones it.

Visceral reaction

A horror film set in a Magdalene Laundry may yet shock critics at home, simply because of the risk that it might be in bad taste. The Channel 4 sitcom, Hungry, set during the Irish potato famine, was panned before it aired over similar questions.

But horror and comedy are linked in the way that our responses are pre-analytical – we are horrified or amused because we recognise something as being true without having to think about it? You either respond or you don’t. It is no surprise that Jordan Peele, who won a Best Screenplay Oscar for Get Out, started his professional career writing comedy.

And like comedy, horror also should punch up – recognising and challenging those misusing their power at the top rather than merely making monsters of those at the bottom. There is nothing we can’t joke about – as long as we joke in good faith. And, similarly, there is nothing in the world so horrific that it is off limits to horror films. Indeed, we will only know it is a horror film if we feel truly horrified.![]()

Aislinn Clarke, Lecturer in Film Studies, Queen’s University Belfast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.