Imagine a brand launched this year. Call it Aura. Aura sells premium skincare. Its founder knows the playbook cold. She’s read every case study, been to the conferences, absorbed the doctrine. And so she does everything right.

The logo is crafted in minutes by an AI tool that generates 40 variations before she’s finished her coffee. Copy writes itself. Photography, those dewy close-ups of skin and amber bottles, is conjured for pennies. Video ads multiply across platforms, each one tested and retested by algorithms that, and I find this detail quietly unsettling, never sleep.

Aura launches with everything a modern brand is supposed to have. The minimalist aesthetic. The founder origin story. The sustainability messaging. The influencer partnerships. The subscription model. All of it.

It disappears within e18 months.

Same playbook, same AI

Not because the products were bad. Not because the founder lacked talent. Aura vanishes because it was indistinguishable from the several hundred other brands that launched the same month using the same tools, the same playbook, and, increasingly, the same AI.

Aura is fictional. But the pattern isn’t, and once you start looking for it, it’s everywhere. Scroll through any product category on Instagram and you’ll notice it. The same colour palettes. The same typefaces. The same photography. The same voice. If you squint, and you don’t have to squint very hard, it all blurs into one brand.

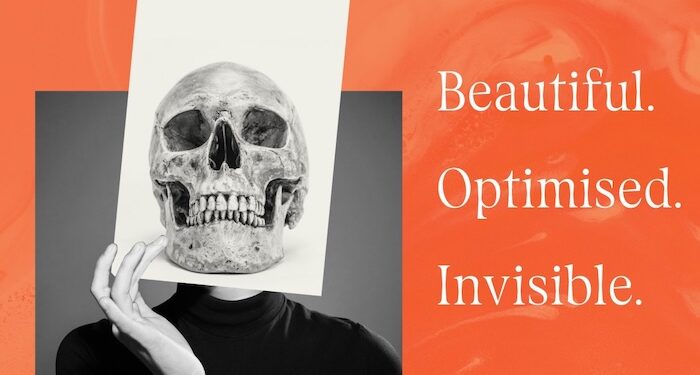

The execution layer of brand building has been commoditised, and it’s not going back. Beautiful content is easy now. Optimised media is easy. All of the things that used to be genuinely difficult and therefore genuinely valuable are becoming, well, not.

Which leaves a question that I think deserves more attention than it’s getting: if anyone can produce anything, what determines what gets produced?

Shared beliefs and cultural contagion

I should say that I’m not the first person to think about this. Heidi Hackemer framed brand as a decision-making framework back in 2017. Tom Morton and Tiffany Rolfe at R/GA formalised the idea of brand as operating system at Cannes in 2023.

Tim Galles at Barkley built an entire methodology in his book Scratch around the concept of a “red thread,” a singular idea that guides every action a brand takes from the inside out. Dr. Marcus Collins pushed it further in For the Culture, arguing that shared beliefs and cultural contagion are what actually move people, not messaging.

They’re all circling the same essential insight: brand needs to function as an organisation’s operating logic, not its aesthetic wrapper.

I agree with all of them. But I keep getting stuck on a question: if brand should function as an operating system, what actually powers one?

This is going to sound like an odd place to look for an answer, but stay with me.

Core narrative

The Catholic Church is not a perfect institution. It has made grave errors, caused real harm, and repeatedly failed to live up to its own principles. I’m not holding it up as something to admire uncritically. But I kept coming back to it because, whatever else you think of it, this is an organisation that has been running, in one form or another, for roughly two thousand years.

And as a study in structural coherence, I can’t find anything that comes close.

You can walk into a Catholic church in São Paulo or Seoul or a small town in rural Ireland and you will recognise, immediately, what you are experiencing. The same core narrative. The same rituals, performed in the same sequence. The same symbols. The same vocabulary. The same hierarchy. The same founding story, told and retold in the same way.

Nobody achieved this with a brand guidelines document. The coherence comes from something deeper: a belief system so embedded in the organisation’s architecture that every person within it, from a Cardinal in the Vatican to a volunteer in a rural parish, can make decisions that are structurally consistent without ever checking with headquarters.

From the view of a strategist

And once I started looking at it as a strategist, I couldn’t stop. A founding figure whose story organises the entire institution. A clear opposition between good and evil that gives actions moral weight. A private language that for centuries separated insiders from the outside world.

Physical symbols that make private belief publicly visible. Rituals that transform ordinary actions into something that feels transcendent. And an internal priesthood whose lives are structured around doctrinal coherence.

You don’t have to endorse any of it to recognise that the mechanics work. And those same mechanics, whether consciously adopted or stumbled into, show up again and again in the commercial brands whose cultural impact far exceeds what their marketing budgets should be able to buy.

I’d been sitting with this for a while when Mark Rukman shared a piece from Nautilus by the political neuroscientist Leor Zmigrod. It crystallised something I’d been circling but hadn’t quite pinned down. Zmigrod’s research shows that our brains are predictive organs, constantly trying to build reliable models of reality so we know what to expect. Ideologies are the brain’s shortcut.

They provide a complete system of answers: here’s how the world works, here are the rules of conduct and thought, here is who belongs and who doesn’t. We don’t have to figure it out for ourselves. The ideology does the predicting for us.

Seductive ideaologies

This is why ideologies are, in Zmigrod’s word, “seductive”. They offer community, meaning, and cognitive clarity in a single package. Our minds don’t just tolerate ideology. They crave it.

Ideology. I use the word deliberately. Not “purpose”, which is what you do. Not “values”, which is how you behave. Ideology is what you believe about how the world works. And I’ve come to think it’s what the brand-as-operating-system conversation has been missing.

The thing that determines whether the operating system actually runs or just sits there looking impressive.

So what does this actually mean for the work? I think, and I’m still working this out, that when AI can produce anything, the only real advantage is knowing what to produce and why. But honestly, that undersells it. Because an ideology doesn’t just guide content.

It guides everything. Who you hire. Where you show up. Who you partner with. What you say no to. How an employee handles a customer complaint without consulting a manual. Which product extensions make sense and which ones would quietly erode what you stand for. It is, if you get it right, something close to an organisational cheat code.

The coherent brand

Not because it makes decisions easy, but because it makes them coherent. Brand stops being a marketing department concern and becomes the logic that runs the business.

And this is where AI changes things. If you have that ideological foundation, AI is genuinely extraordinary. You can express a coherent brand across more touchpoints, faster, at a scale that was logistically impossible when everything had to pass through human hands. You know what to make because you know what you believe.

If you don’t have it, you get Aura. More content. More campaigns. More touchpoints. All of it technically competent, none of it meaning anything.

I’ve been working on something longer that goes much deeper into this. Religious movements, political campaigns, high-demand groups, and why the structural overlap with the strongest commercial brands is not metaphorical but mechanical. If that sounds interesting to you, I’d love to hear from you.