If you like independent, art-house films or other specialised movies, you may have heard of the Romanian comedy-drama Sieranevada, which was released in 2016. The film was formally premiered as part of the main competition programme of the prestigious Cannes Film Festival and was subsequently shown at other international film festivals, including Toronto, New York and London.

Due to its success on the festival circuit, Sieranevada was reviewed by 48 international film critics, and received a positive rating from 92% of them. Among these were UK-based trade journals, such as Sight and Sound and Screen International as well as mainstream newspapers The Guardian and The Telegraph. But while this publicity generated audience interest in the film, it has yet to secure distribution that would allow UK audiences to actually watch the film – it’s not in cinemas, on DVD/Blu-ray, nor on online video-on-demand platforms (VOD).

The development of VOD has provided new opportunities for films to reach audiences. In particular, specialised films with traditionally limited distribution opportunities have taken advantage of this development. But are online audiences presented with an endless choice? Not really. So why is this?

The digital film revolution

In the mid-2000s, digital utopians such as Chris Anderson were already arguing that an endless choice of specialised and niche content would become available to online audiences.

And more than a decade later, it’s true that distribution opportunities have increased for such content in the online market. Film audiences are able to browse through catalogues on transactional VOD platforms such as Amazon Video, Microsoft and iTunes where they can find tens of thousands of films.

But there is still a significant proportion of films that remain inaccessible for audiences, even if – like Sieranevada – they have been selected for prestigious international film festivals.

Amazon.co.uk, Author provided

What is available?

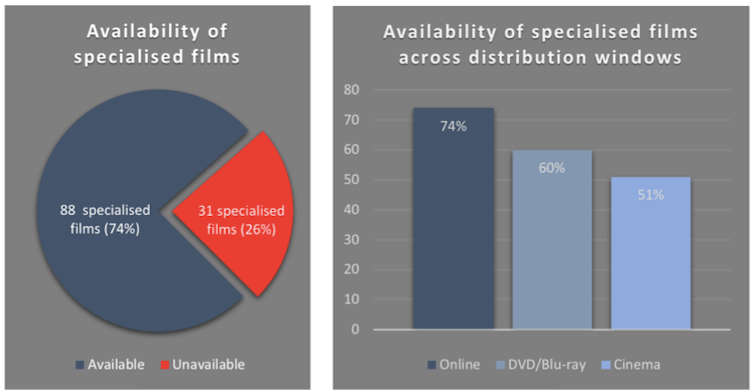

In an effort to identify the proportion of well-regarded specialised films that reach audiences in the UK market, I analysed a sample of 119 such films shown at prestigious European and US film festivals in 2016. My analysis in the graphic below confirms that the online market creates distribution opportunities for a greater number of films than the theatrical cinema and DVD/Blu-ray markets:

- 88 specialised films (74%) were given an online release on Amazon, Microsoft or iTunes

- 71 specialised films (60%) were given a DVD/Blu-ray release

- 61 specialised films (51%) were given a theatrical cinema release

BFI weekend box office figures, Amazon, Microsoft, iTunes, Author provided

But while access to specialised films has increased, 26% of specialised films remain inaccessible for audiences on any format. That is a remarkably high percentage – given that it is relatively easy to secure online access for films.

My analysis includes a sample of specialised films selected for some of the most prestigious festival programmes, but it is likely that online availability is more limited among specialised films selected for less prestigious competitions. So why can’t online audiences see any film they want? It’s to do with the way the industry works.

Why can’t we get everything?

In the film business, sales companies have an important role to play in the process of enabling access for films because they negotiate distribution deals with a range of distributors in international markets. But if sales companies are unable to sell distribution rights, they retain control over the distribution and release of those films.

The development of the online market, in this respect, has opened up opportunities for them to work directly with VOD platforms or with content aggregators, who work as intermediaries between rights holders and VOD platforms. Examples of such content aggregators include The Movie Partnership, Juice Worldwide and Gunpowder & Sky.

For instance, the comedy-drama Dreamland (2016), directed by Robert Schwartzman, premiered in the US Narrative Competition of the Tribeca Film Festival. The US sales company FilmBuff (now named Gunpowder & Sky) acquired worldwide distribution rights. In the UK market, the film was not released in cinemas or on DVD or Blu-ray, but FilmBuff made it available in the online market through direct connections with Microsoft and iTunes rather than via a UK distributor.

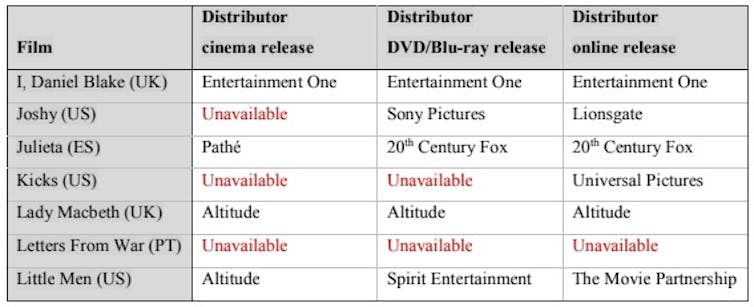

Despite such opportunities, sales companies do not always work with content aggregators or directly with VOD platforms to make specialised films available if they are not picked up by distributors. Making films available online requires organisational effort and a low-cost investment in digital formatting, but returns on investment can be very modest. That explains why some films remain inaccessible to audiences – as demonstrated for the UK market in the table below.

BFI weekend box office figures, IMDb, Amazon, Microsoft, iTunes, Author provided

Endless choice

The politics behind the process of providing access to specialised films ultimately affects producers and audiences. In the new digital economy of attention, producers demand wider distribution for their films, while audiences demand endless choice.

This issue needs to be resolved. First, it needs to be addressed in film industry discussions between film producers and sales companies. In particular, sales companies should make a stronger commitment to making films available on transactional VOD platforms.

Second, policymakers can intervene in the process of making specialised films available online. Public funding agencies, such as the British Film Institute (BFI) in the UK, provide substantial financial support for the production of specialised films. They can provide more distribution incentives to support cultural diversity in the online market for films in the UK. This would help to support greater cultural diversity, democratisation of access to films and enhancement of consumer choice.

While cinema goers have always had limited options when it comes to the number of screens they can see their favourite art house movie on, the internet era was supposed to bring with it an endless choice. But what is becoming clear is that this utopian dream is still far from being realised.![]()

Roderik Smits, Research Associate, University of York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.